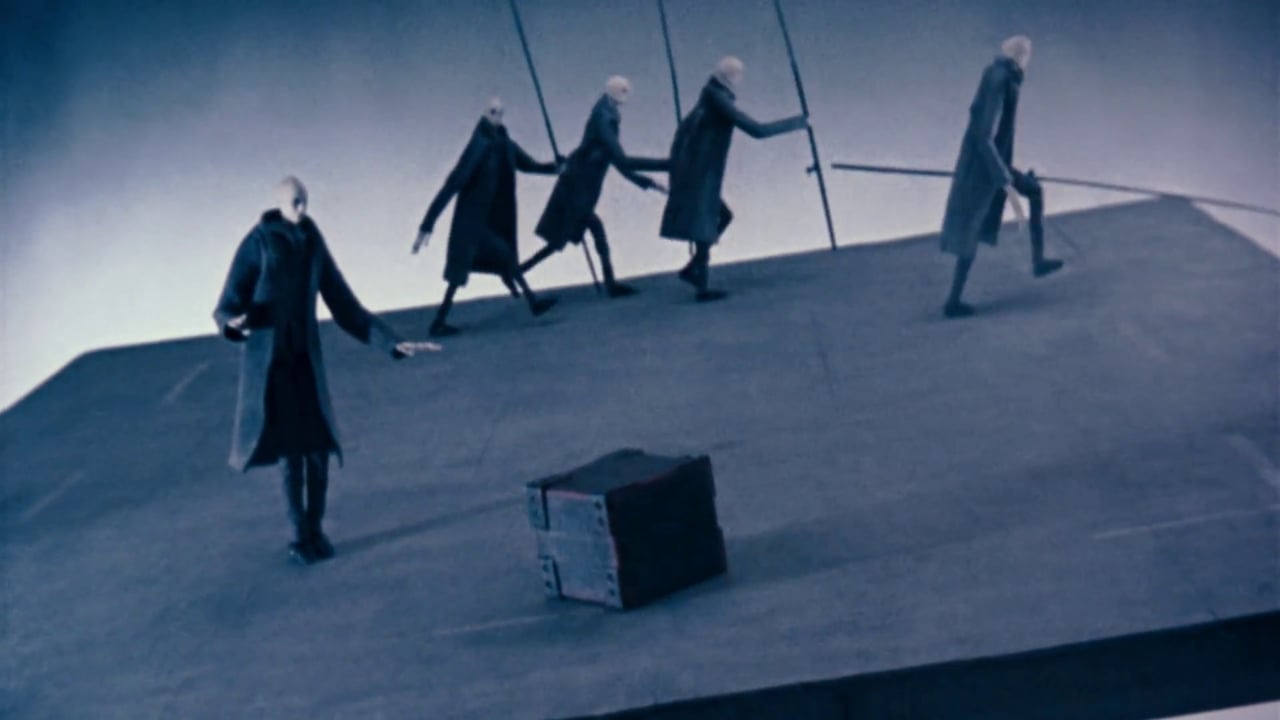

A platform floats in a neutral space. Strange men, identical except for the numbers on their back, appearing as though out of some dystopian future, must work in concert to prevent the platform from tipping. The emergence of a strange box, a new development in this closed and sterile space, disrupts the tedium but also the teamwork, as each man wants to individually inspect and enjoy the box—threatening them all as the platform becomes increasingly unbalanced.

Directed by German brothers Wolfgang and Christoph Lauenstein, Balance is a remarkable piece of animation that has held up very well through the years. Winner of the Academy Award for Best Animated Short in 1989 , it has been featured in a few animation collections on video, including the now sadly out of print, “The World’s Greatest Animation”, where it headlined alongside another famous film we reviewed on this site, Nick Park’s Creature Comforts. But thankfully the internet has saved us once again and this film has been uploaded to at least half a dozen user-generated content sites. These uploads might be unauthorized, but I doubt the Lauenstein brothers care as it is sure to act as a great calling card for their commercial film production house.

In fact, Balance is a perfect reel highlight for commercial direction because it displays simple confidence in concept. The film uses stop-motion to animate, but is ultimately not much to look at. It is not pretty and the character motions lack the artistry and polish of some of the more experienced practitioners of the craft. When made though, Cristoph was still in school for his Fine Arts degree. So, in the midst of such brilliance, this shortcoming is easily forgiven.

What shines here instead is idea and execution. A film without words like Balance is frequently an exercise given to young animators and film students alike. New storytellers often overwhelm audiences with exposition, so instead are asked to concentrate on telling a story visually, focusing on expression and craft to carry a viewer through. It is difficult enough to simply tell a story that makes sense, let alone interest your audience, let alone raise greater social issues, all of which Balance does.

In execution, the film is accomplished. The cuts do a fine job of relaying the action, the physics of balance are realistic enough, and key actions by characters are imbued with a forceful purpose. Several memorable shots punctuate the film and prove haunting. As an idea, it works as a parable and an allegory, and more remarkably the two contrast. It strikingly moralizes the dilemma of human beings working in cooperation. Like a story out of Game Theory, if the men were to cooperate they could all enjoy the box together, but it is selfishness that dooms them.

Add though a context. A time and place to the film’s creation. Germany, 1989. If you do, you realize a whole host of additional readings and levels are available to enjoy. The fact that the men are identical but for their numbers, is this not a oft-used symbol for the anonymity desired of those in a Communist society? That they are all the same and thus interchangeable? The cooperation they display at first is perhaps indicative of Socialism, and the box, what is the meaning of the music it plays, the dancing it inspired? Radio Free Europe used to broadcast American music, such as the jazz heard coming out of the box, into Communist countries throughout the Cold War. Perhaps the box is a symbol of possibility, of what is outside the closed system, which inevitably undermines said system.

And so a parable about selfishness becomes an allegory about German society and Soviet Communism at its fall. The sad and ironic ending of Balance, who is at fault? The men that fail to do what is best for them? Or the system that fails to acknowledge this human quality?

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi