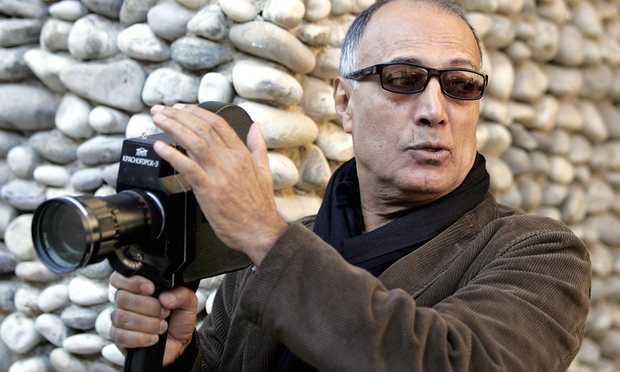

The international film community mourns the passing of one of its greatest masters this week. Abbas Kiarostami’s films are intimate, contemplative pieces that pose complex questions. For many, his work also served as an introduction to Iranian cinema. His best known films are perhaps his 1990 masterwork Close-Up, which stands as one of the finest examples of a documentary drama hybrid (long before this type of genre fusion became ubiquitous on the film festival circuit) and 1997’s Palme d’Or winning Taste of Cherry.

Despite his international success and recognition, Kiarostami continued to make short films throughout his career, allowing story and content to dictate form rather than vice versa. His very first short, The Bread and Alley (1970) has a neorealist feel and demonstrates what was to become the director’s signature use of extremely, sometimes uncomfortably long takes. It was floating around video networks this week before being taken down, and if you can find a (legit) version to watch, it is worth your while. Watching the little boy kicking a piece of rubbish along the street in a long tracking shot at the beginning of the film, it’s hard not to be reminded of the famous rolling aerosol can shot from Close-Up, 20 years later.

In Orderly or Disorderly (1981), another Kiarostami formal signature is at play. The director draws attention to his own presence – leaving the calls of “Cut!” at the end of each scene audible, and showing us the clapperboard. Frequently switching to an aerial angle, he emphasizes the disparity between order and chaos, and how the two can co-exist in spaces occupied by large numbers of people – in this case, a school. At this point Kiarostami worked for a state organization called the Center for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, and many of his films center around children, often in a pedagogical environment. Later in the film he switches to a busy traffic intersection without explanation – allowing the viewer’s mind to make the leap and understand the witty visual parallel line he is drawing.

Several of these early short films of the director’s are available to those who search online, and have appeal to Kiarostami completists. Many of these works are experimentally formal in ways that highlight Kiarostami’s early career as a graphic artist. But even after his rise to international fame, Kiarostami continued to create in the short format. One of the more intriguing examples is Roads of Kiarostami (2005), a 30min short that reflects upon the power of landscapes via b&w photography. The film is undoubtedly stark, but nonetheless fascinating in its poetic observations — a meditation on art, nature, and creativity. With an easy transition between essay and autobiography, Kiarostami blends the filmic and documentary with a deft hand, only with the unexpected shadow of geo-political turmoil raising its head by the end.

Kiarostami’s last short film may be slight, but like most of the director’s work it is worth your time. This short film from 2013, made as part of the Venezia 70 Future Reloaded (70 shorts made by renowned directors to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the iconic Venice International Film Festival) is only a shade over 60 seconds long, but in it he again draws attention to the presence of the camera, and inserts us in a scenario where there are more questions than answers.

It is unfortunate that, like so often is the case, it has taken Kiarostami’s passing to force such a wide-ranging appreciation of his life and art. Kiarostami’s profoundly human work served as ballast to Western impressions of his country through the fraught decades post-revolution, and his influence has filtered through to our modern golden age of inquiring, reflexive documentary filmmaking. His legacy is secure, and his cinematic preoccupations will continue to direct filmmakers the world over for a long time.

Penelope Bartlett

Penelope Bartlett