I don’t actually know too much of the back story about how the feature came to pass, so I’m going to do a cop-out first question and just ask you gents to walk me through the timeline from the short’s South by Southwest premiere to today.

Zeek: Yeah, it was a long, long process, and we’ll try to keep it concise. So we made the short film, it was released at South by Southwest in 2014, and then it took 3 years to get the feature made. The short film went online and there was immediately interest in it, and we—at that time we were already working with Scott Glassgold (editor: a famous manager in the sci-fi shorts space who is a producer on the feature) who picked us up off of In the Pines, and he set up a whole bunch of meetings in LA. At that time we didn’t have a feature script, but obviously there was a lot of interest in Prospect, and so, based off of that, we decide to go off and write the script ourselves and then come back in and try to sell it on our own terms. At that time we did sign with WME, and we did partner with Chris Weitz’ company Depth of Field, who jumped on as producers. So then yeah, we went back and wrote the first draft of the script.

So, to the Depth of Field relationship and the WME relationship, did that come directly out of SXSW, or directly out of the online release or…I guess the two were pretty close together right?

Zeek: Yeah, but I’d say we’re all about the internet. Particularly with our short film In the Pines, which was the first short we had at South by Southwest—the festival was an incredible experience and definitely gave us that stamp of approval—but it took putting the short online to actually get into Hollywood, and I would say the same was true for Prospect. SXSW gave that stamp of approval, but getting it online was how it traveled around town. There weren’t a lot of agents at SXSW, they were watching shorts on the internet. So that’s how we got all those.

…it took putting the short online to actually get into Hollywood…

Chris: Yeah it’s interesting. With In the Pines we definitely did the whole festival tour and wanted to do all the festivals we could, which, talking to other short filmmakers, is pretty common. But after that whole experience we discovered that things really started happening when we put it online. The festivals were great for for meeting people, they were great for connecting to other filmmakers, and for us—particularly being up in Seattle where the film community is pretty small, a place like SXSW really opened up our perspective. But taking that experience when it came time for Prospect, which we made very intentionally to be a calling card for a feature film, we didn’t really bother. We played SXSW, and we believe that playing a higher-tier festival—that stamp of approval—really does a lot for your film, but as soon as we did that premiere we wanted to get it online as soon as possible and generate as much buzz. It kind of started to be whispered about in Hollywood, and we followed up and did our first real big water bottle tour trying to pitch the feature.

Yeah that’s cool. Obviously I’ve talked to a lot of filmmakers over the years, and that generally lines up with the impression I get from them. Folks are always a little bit dumbfounded when we’re giving them the advice that the online release, as far as your future prospects going forward are concerned, is actually the primary release. Really shoot for your big, top-tier festival premiere and do anything you can to get into that of course, but then, once you’re done with that, the rest is mostly for if you’re going to be there in person. (For more background read our article “Be Everywhere All At Once“)

Zeek: Yeah, and I feel like, just from an industry perspective, if you can get a lot of views that’s going to be a lot more quantifiable of validation for the project then however many laurels you can accumulate.

If Prospect was always designed to be something of a calling card for a feature, how come you didn’t have a script ready for when you were taking all those generals?

Zeek: (Laughter) Because we made a mistake! As much as…that was maybe one of our biggest lapses in this whole process. But what I think that yielded was unpreparedness for our first round of meetings. We scrambled together a treatment of our vision for the feature version of Prospect, but when it came time to pitch—and this was our first time trying to pitch in Hollywood—it was a very overwhelming, intimidating experience. Our first pitch was at Bad Robot, which, in a lot of ways in retrospect was fine, because we didn’t really have much of a shot there anyway, but it went terribly. It was one of the most cringey moments of my life, because we just had a loose grasp on the story. It was very fresh and you need to be able to talk about it passionately and naturally. But we were still capitalizing on some of the heat from the short film, we managed to acquire partners in our producers at Depth of Field and our agents at WME off the short primarily, and it really became a pitching boot camp. We were able to sacrifice a lot of those initial meetings in order to get that experience under our belt so that the next time that we went out with a script we could be more confident in the room.

We scrambled together a treatment for a vision for the feature version of Prospect but when it came time to pitch—and this was our first time trying to pitch in Hollywood—it was a very overwhelming, intimidating experience.

Chris: But this is the thing, getting back to your question—to me in retrospect it really didn’t matter, because even if we had a draft of the screenplay, and later on when we did actually have a draft of the screenplay and there was financing interest, I was really glad that the film wasn’t greenlit—we weren’t ready. Because what preceded was we spent three years trying to secure various financing partners and we had…I think we had three or four financing deals fall through, and in that time we re-wrote the script, a very full rewrite at least twice, and then another kind of minor rewrite, and we also kept making more concept art and forming the unconventional production design approach that we used on Prospect which was to open our own production design shop. It took a lot of convincing to get our eventual financier Bron to take on the project, but we really needed that development time to get our shit together and figure out how we were going to do this.

Obviously it worked out for you, and when people see the feature they will see the fruits of that approach. The worry that comes immediately to my mind with that kind of prolonged process is how real is heat as a concept? Was it harder to go ahead and get those meetings 2 years after the initial buzz around the short?

Zeek: I don’t know. We definitely took it back to some of the people we met with initially and there was some follow-up there, but I think the first financing partner (that fell through) we didn’t meet in the first round, that was someone WME brought in later. One strategic move we made was that Depth of Field, Chris Weitz’ company, was also represented by WME, whom we chose to represent us. So in a lot of ways, as small-time filmmakers at a big-time agency, it’s hard to expect much of anything from your agents…should I say that publicly? (laughter)

But, you know, it’s really difficult—these agents are representing much more impressive clientele, so it’s difficult to get their attention. But because our producer Chris Weitz was also represented by the agency I think they did put more effort into trying to find us financing partners, and that’s where all the following attempts came out of.

Chris: Yeah it was a strategic move to combine powers and consolidate everyone’s focus. It was kind of a steady stream—every now and then we’d go back to Seattle, we’d work on the script, we’d work on art for a month or two, and then, once WME, Depth of Field had secured some more interest and it warranted flying us back down to LA to pitch again, we would just be periodically doing that. I will say that one of the things that we didn’t anticipate from this whole experience was how much of an emotional grind it was. With all the sorts of starts and stops, and these kind of roller coasters. Particularly for your first feature you get to the point where you are poised to possibly go into production in a month, in a few weeks if this deal comes through, and then for it to all fall apart. You put your whole life on hold and then it falls apart, and it’s a big whiplash, and it can turn into an existential nightmare at times. One of the ways that we tried to cope with that was to always go back to the material and see how we can improve it. I do think that over the course of the three years that it took us to secure financing—a lot of circumstances were involved, a lot of luck is involved, but at the same time, every time we went back out to pitch it, it was a little bit better, we were a little bit more confident, our plan was more secure, and by the time we got financing we had—inspired by Jodorowsky’s Dune—we had a big coffee table book full of art that we could slam down on the table in pitch meetings, we had a bunch of loose leaf designs, we had a new and improved script, and we had a constantly refined budget, to the point where we had an almost ready-to-go package that was ready to execute immediately. I think that all those efforts aided in getting the green light.

That sounds amazing. I hope the coffee table book gets some sort of future life.

Chris: It was really cool. Some of it is a bit dated now, but it was a big, big hardcover book.

So how much of your bandwidth during this period of time, with the fits and starts, and the digging back into the material—how much of your life is Prospect versus anything else? Versus Shep Films and your commercial productions…I mean you have to be supporting yourself somehow during this I imagine?

Zeek: Yeah we were making commercials that whole time, and learning more by doing it. Neither Chris or I went to film school, and during those three years we kind of kept at higher-level, bigger-budget commercial work that allowed us to keep shooting and trying things out and experimenting. As far as the time division, it’s kind of hard, because it came in bursts, but I would say it was either a 1/4 or a 1/3 Prospect and 3/4, 2/3rds commercial work?

Chris: Yeah I would say we were working with a lot of collaborators like our production designer and some of the prop and set designers to develop this concept art, and they all had day jobs, so that was all nights and weekends for everybody. Our commercial production company was a full-time job, but we were also able to, when we needed to, take a few weeks hiatus on commercial work and clear our schedule so that we could focus on the script. But we also still had to be paying rent somehow.

Zeek: We also developed other material. We’re developing a pilot with Amazon right now that’s based off of a screenplay that we were working on when supposedly Prospect was not happening.

A view of Prospect’s production design warehouse.

A lot of it sounds like simply putting in the work in refining the concept, refining the materials, honing the pitch…I don’t know if you’re able to speak to something outside of your experience more generally, but I look back at that time around 2014-2015 which I think of as a heyday for the sci-fi short film calling card, and there was a lot of buzz around the format, yet very few of those filmmakers have gotten to the finish line like you did. I’m wondering what was the vibe you were getting while taking all those generals at the time, and was there anything particular that you learned through all that pitching, or that you feel that you did that was different, or special, that helped you get over the finish line?

Zeek: I don’t know if we have the perfect perspective for that, but one thing is that Prospect is still an indie low budget film. You know, we weren’t pitching it to be a $50M, $100M studio movie, we were pitching it to be a small movie, and by this unconventional plan of a really long lead time, and opening up our own production design warehouse, we were promising to make a lot of very impressive practical production design for an extremely low amount of money. So we were kind of a weird deal, and honestly a lot of people were interested until they heard that we weren’t going to fit into any sort of standard mold that they had made, and then things generally didn’t work out. It it really took Bron, who had a former line producer upgraded to head of production who actually looked through the physical merits of our plan and realized that we were doing something that was going to create a lot of value for the investment.

You know, we weren’t pitching it to be a $50M, $100M studio movie, we were pitching it to be a small movie, and by this unconventional plan of a really long lead time, and opening up our own production design warehouse, we were promising to make a lot of very impressive practical production design for an extremely low amount of money.

Chris: Yeah we had this kind of weird vision for the execution where we were asking for 7 months to a year for pre-production and a 40 day shooting schedule, and all this for a low low budget indie operation, which just isn’t par for the course. For a lot of financiers that just didn’t add up, and it almost felt antagonistic to us getting a green light, but we just kind of stuck with it because it was the only way we saw this being viable. As the plan got more refined and specific, we were able to show what our vision was more clearly, until it landed with somebody.

That’s interesting, that your indie budget sensibilities are, on the one hand, an asset, but in some ways you’re saying that it was also a demerit, because a studio low budget film is still 5-10 million dollars and I assume you’re coming in well under that—more like Sundance indie right?

Zeek: Yeah. From our perspective it was an asset because we were thinking it through and it was informing every part of the development of the film—we were writing to this production strategy and this budget, and we were able to calibrate the material to match it. To us I felt like this great deal, this integrated production strategy, and we were just struggling to communicate it to people. I think the disadvantage was more on an optical level because it was unconventional and that was scary to a lot of people.

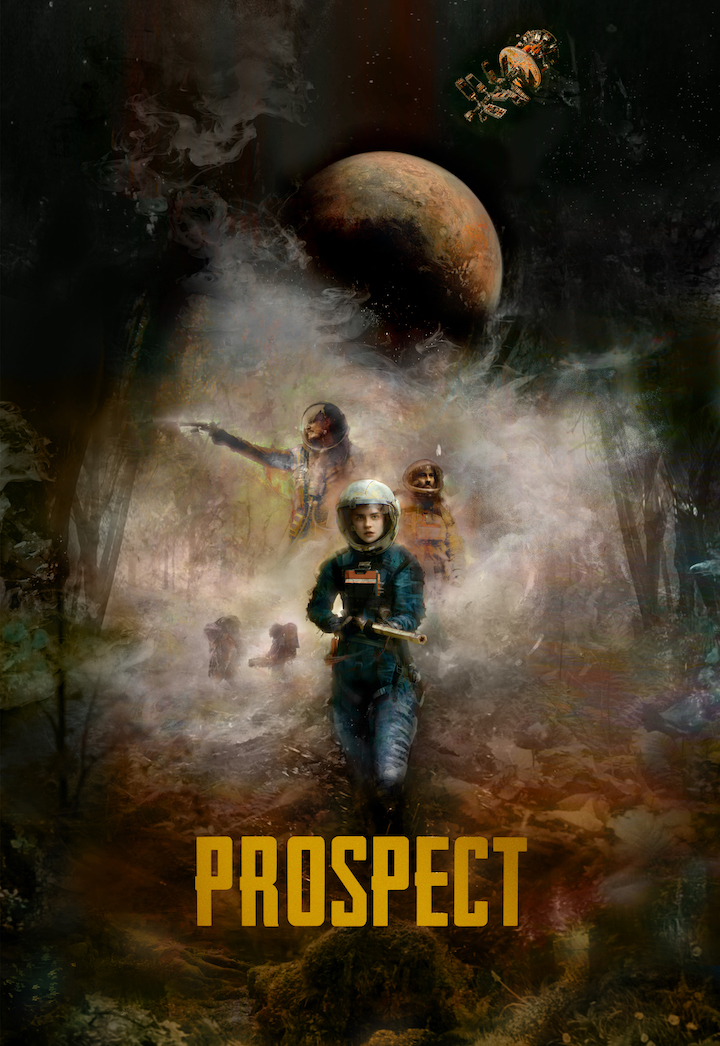

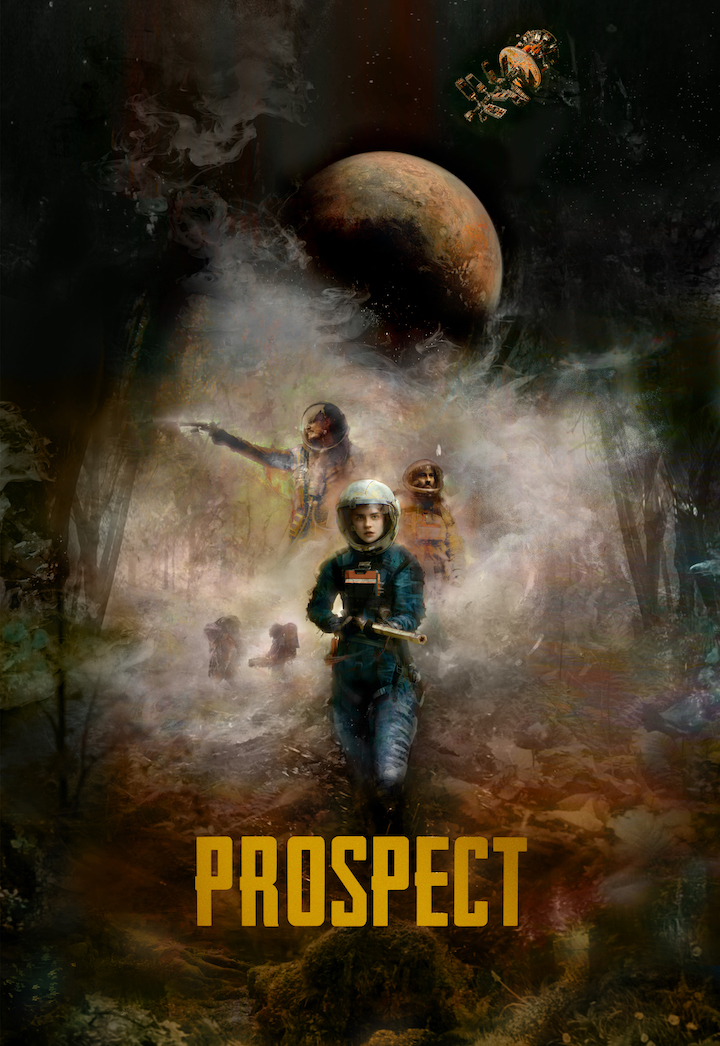

Prospect’s poster designed by Chris Shy.

Kind of shifting gears now to the film itself, your fidelity to that gritty, practical style that showed itself in the short is pretty remarkable. Did you ever feel any pressure to move away from that, or to make it bigger? The film does include some CGI, like the establishing shot at the station before they head out, but overall I was really surprised at how much of the original short’s DNA ended up making it into the future.

Zeek: Yeah. Thank you. We definitely wanted to start in outer space to contextualize the moon itself and so, since we couldn’t go and shoot in outer space, we had to bring in some CG. But we always set really hard rules about that so that every time you see a spaceship it’s actually shot through a practical window so that the texture of our vintage lenses and the feeling is still consistent even if it involves computer-generated elements. We wrote the script three times and the first rendition was maybe a little bigger, but I mean, not much. It was always meant to still kind of keep the Western DNA–where it’s a small group of people on a frontier where there’s no law, and where every interaction is its own transaction.

Chris: While we were perhaps a few steps behind when we released the short film by not having a script, one of the things that was always a given, and was thoroughly established in the short film, was the texture of the world, and that was never something that we called into question. It was integrated into the narrative as being this kind of blue collar, small frontier story. We’re not talking about heroes fighting over the fate of the universe, it’s people who are struggling to get by, and in that kind of Western spirit, it’s individuals, freelancers carving their path out on the frontier. So that was always part of the premise, and then also from a production standpoint, from a textural standpoint, drawing on the classic sci-fi films from the 70’s and 80’s: the original Star Wars, Aliens, the original Blade Runner, stuff that is very practical focused. That was always such a tenant of our production design philosophy that we really wanted to push the limits of what we could do with an indie budget in the realm of production design in rendering this world physically, and with the props and sets and costumes, as opposed to green screen backdrops and CG spectacle.

One of the things that was always a given, and was thoroughly established in the short film, was the texture of the world, and that was never something that we called into question.

I’m going to try to say this the right way so that you take it in the way that I intend. <laughter> There is something magical about the fact that the “aurelacs” are in these white cases, and if you’re viewing the film skeptically you think, “well that’s just a Pelican case”. But you guys managed in the feature to be on the right side of that line—and it’s a very fine line—between minimal and rugged world-building and what could be perceived as amateurish. So how do you feel that you were able to walk that tightrope, and get audience buy in? Is that something that you felt very cognizant of during the design process?

Zeek: Absolutely. You have to set very very strict rules. We created a production design bible that had extensive references for even just the geometry of everyday objects. So even if something was off the shelf, it had to go through a rigorous vetting process to make sure that it fit into the Prospect world. And then there was a lot of subtle details like the only blue that’s allowed in the whole movie is on Cee’s space suit and a little bit on her sweatshirt, and some of her hero props. We omitted allowing blue to be used on any other prop ever. I was constantly going around in the shop telling people they can’t use blue, kind of being very strict and fundamentalist about it. It doesn’t really matter what techniques you’re using because this way it will feel internally consistent.

Chris: I feel I’m going to take a shot at addressing at what I feel you’re getting at. One of the strategies that helps pull some of the stuff off was that we wanted to create as dense a tapestry of these production design details as possible. We wanted every frame to feel as full as possible with all this stuff. The second something feels spare, or just a little too shallow, it starts to feel contrived. It’s evidenced in some of the graphic design approach, with a lot of the little details with cartoon characters and advertisements and branding on all the objects—we wanted to try to compensate for the amount of detail you get in the real world to lend it that reality, and I think, particularly with you’re working with limited resources, there was a bit of a compensation for that with with detail and hurling as much stuff onto the screen as possible to make it feel real.

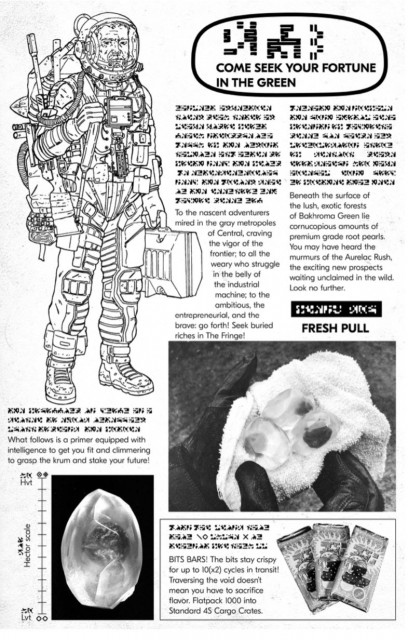

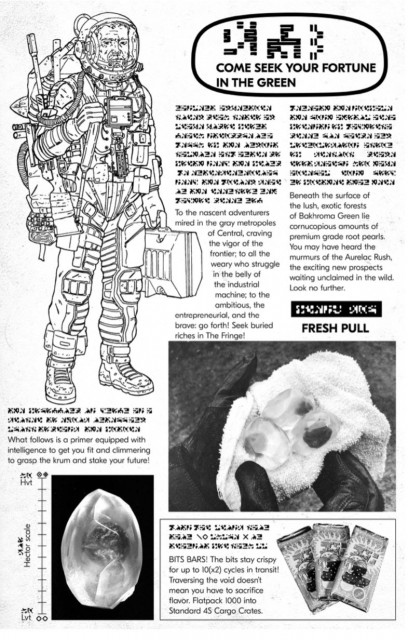

A page from a promotional “playbill” designed for the film’s theatrical release

I don’t think that would have occurred to me, but as soon as you said it I realize that, yeah, I agree wholeheartedly. It jives with my experience, having watched so many sci-fi shorts. Something that you really notice with a lot of the production design in these shorts is that a team just uses a normal, contemporary setting or a location, and they just add a couple of little elements here or there, and it really sticks out like a sore thumb. When you just slap on some digital UX onto something that is recognizably contemporary. I think that the detail that you are describing is part of the reason you’re able to overcome that. So that’s really cool.

Speaking of detail, I the denseness you describe certainly includes the script, because you guys—and this seems like a deliberate part of your world-building strategy—you guys throw out a lot of terminology and lingo that is relatively unexplained. I think that the film is pretty remarkable for how little exposition you provide, you just kinda throw the audience into the scene and expect them to catch up. Describe a little bit your strategy and thinking in that regard.

Zeek: I mean it’s always great when people identify that, because it was very much the intention. I think it’s definitely a factor of taste for some people, but for us, one of the most compelling things about interacting with science fiction is that feeling of immersion, and this goes back to our experience as kids with these rich worlds, and we wanted to bring that richness to Prospect, and part of how you achieve that, from our point of view, is by getting dropped in over you head into a world. In some ways tactically, and in some ways it’s just part of this more intimate, coming-of age layer of the film. The entire film is through Cee’s eyes, and we never wanted to compromise that perspective. We wanted to keep as much exposition out of the character’s mouths as possible, we didn’t want them talking about things that they wouldn’t actually be talking about, and also on the flipside, there are a lot of things that go unexplained, that are sort of just tangential detail in the world. They were the end result of a lot of production design conversations around backstory, and what cultures do these side characters come from and whatnot, but if it wasn’t relevant to Cee’s immediate experience, it didn’t warrant over-explaining or digging into, or diverging from, the main story in the film itself. It’s these details I just love in other films, is when you see a few seconds of a character and it stokes your imagination of what’s going on with them, and it’s those details that cross the line, where this universe wasn’t purpose-built for this story, this universe exists, and we are just observing it. So a lot of that was intentional to try and create that feeling, and always chasing immersion, and always chasing the feeling that this world is real.

So I feel pretty strongly about this because Short of the Week is a creative partnership between myself and my co-founder Andrew, so I was curious a little bit about your working relationship as dual-directors, and how does that work? What are the strengths of that kind of approach, do you have division of responsibility in a delineated way, and does it have any drawbacks?

Zeek: For Chris and I, we haven’t really done anything else. We started doing commercials together right out of college, and did our first short films together, and then of course did Prospect together, so the evolution of how that functions has been very organic. Generally speaking my strengths are more visual and structural, and Chris is a master of the language when we get into the writing processes. That kind of partnership allowed me to be the cinematographer on Prospect, which was still a lot work—I’m not sure i want to do that again—but definitely it allowed for that space to happen. I think it was funny, some of the crew informed us after the shoot that they would figure out who of us to ask about what, because there were clearly different details and facets that we had very naturally sort of divided up.

Chris: I think a lot of it is innate chemistry, that was sort of developed over the course of running a business together for years. Even on the set of Prospect we were still kinda figuring it out, but we had a very innate sense of each other’s strengths, when to defer to each other, and when to challenge each other. When we started our commercial production company, it was just the two of us doing everything: from biz dev to accounting to concepting, production, post—so we had our fingers in every step in the process, so that was a very good way to get to know how each other worked.

Zeek: A feature, especially a first feature, and a fairly ambitious one such as ours…it’s just so hard! It’s so much work, that this was one of the most harmonious collaborations between Chris and I because we were simply thankful to have each other for support through that process and share this insane workload.

Chris: to get a bit more specific, one of the other elements that helped it work, was the fact that we wrote the film together as well, and we worked on writing it for so long, that by the the time we got to production there was very little left to disagree about because we had already hashed so much out together in the creation of it. Like if we were co-direct something someone else had written, I think there would be much more premise for disagreement in the moment, or a different interpretations of things, but for Prospect it was such a personal development process that we were both intimately, involved in, that we were very much on the same page during all of production, creatively.

The director’s during a costume fitting

Zeek: The last thing maybe worth mentioning on this topic is that it was really cool having Jay Duplass on set for the first couple of weeks. I closely followed the Duplass Brothers in college, and when we got the opp to work with Jay, it was exciting on multiple levels. He had a bizarrely similar experience—he personally shot him and Mark’s early films that they co-directed together. So on the set of my first feature film, while I’m holding a camera, the guy right in front of me is positioned to have the most empathy for what I’m doing, more than almost any other human being in the world. He gave us a ton of advice and a lot of tips, and was so much more than an actor and really mentored us a lot during that first part of production.

Following that same thread, I guess last question- you can work and prepare, and do as much conceptually as you can, and do as much pre-pro as you can, but no matter what filmmakers i talk to and how experienced they are, you are never really READY—especially when it comes to a first feature. So talk a bit about the fears you had to overcome, or some of the surprises when it came down to actual production.

Zeek: It’s not a very sexy answer, but the number one thing snuck up on me and that I didn’t anticipate, was how much more intense time-management is on a feature set. It’s everything! If you can’t coordinate departments correctly, and things get off schedule, the quality of your film directly sinks. That’s the one thing that doing shorts and commercials didn’t really prepare us for, because they are such a sprint and when you’re in the marathon of a feature film that sort of management is something you need to learn very quickly.

Chris: For me, walking onto set the first day, that feeling of what am I doing here? And that insecurity, that imposter syndrome, nothing can fully prepare you for the scale of your first feature aside from doing your first feature. What I clung to was the story. Essentially, the fact that I knew that I was the prime authority on this story and I was the one who could speak to it the most effectively, and a lot of that went back to thorough script breakdowns and trying to over-compensate as much as possible with prep, and cling to the things that I could anticipate, the things I could prepare for, so that wasn’t what was causing problems when all the other variables come into play. To limit the amount of stuff you’re going to have to figure out on the fly as much as possible, and for me that meant trying to find as much creative confidence as possible, to compensate for all the other lack of confidence in the things we were not prepared for.

Thanks gentlemen! We appreciate the time!

Prospect is expanding to theaters across the United States today, distributed by DUST. Visit the film’s website to find locations near you. Digital and VOD has not been yet announced, we will update you when we know more!

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi