Few films encapsulate the pregnant possibility of short-form storytelling better than We Were the Scenery. It is stuffed with potent strands of storytelling and inquiry, and yet, in its restraint, it veers dangerously close to satisfying none of them. It alternates between a daughter’s archaeology of her heritage, the reminiscences of refugees, an anti-war polemic, a dissertation on media representation, and an experimental video tone poem, yet with only 15 minutes to work with, it doesn’t want to be boxed in or fully commit to any of these. This film is the endpoint of a larger multimedia project and, mirroring the density and malleability of its discursive components, it has taken several forms—a multi-channel art installation, written prose, as well as poetry. It’s as if director Christopher Radcliff and writer Cathy Linh Che understand clearly the complexity and ineffability of the large themes they are trying to engage, and realizing the futility of their comprehensive capture, instead opt to approach them obliquely, in order to do more justice to the fullness of their subjects.

Explicitly, the film centers on Linh Che’s parents, Hoa Thi Le and Hue Nguyen Che, who dramatically fled Vietnam in the turmoil of the war, and how, as refugees in the Philippines, they were rounded up and bused off to play small roles in one of the defining classics of film history. They are equanimous in their recollections, but there is clear tragic irony in hearing of their experience performing a conflict they had only recently escaped from.

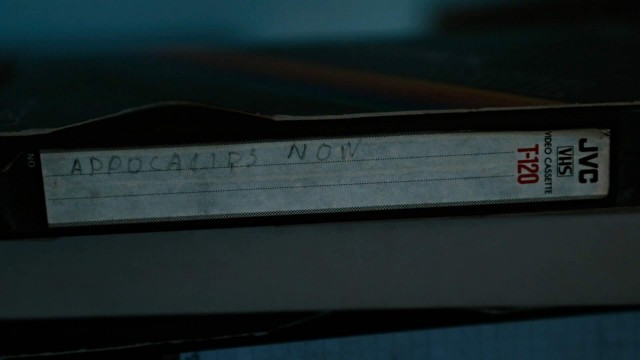

Their story is an intriguing hook, and is, of course, catnip to cinephiles, so it makes sense that The Criterion Channel has licensed the short, though fans of Apocalypse Now will not find a ton of fresh material. What will appeal to that audience, and what surely impressed the jury at Sundance this year when it awarded the film the Short Film Jury Award for Non-Fiction, is the artistry the team has brought to bear. This is not a standard talking-head short, even though Le and Che’s interviews comprise the entirety of the film’s dialogue. Visually, the film is hypnotic. The footage is relentlessly flowing, employing a mix of sources: purposeful and directed contemporary shots, archival home movies, Super 8 observational footage, poetic B-roll of Vietnam, and, of course, fuzzy footage of Apocalypse Now, via the couple’s only copy of the film, a degraded VHS tape they recorded off the TV.

Shot expertly by Jess X. Snow, who is also a producer of the project, and edited by Radcliff, it is a subtle and affecting montage that plays a vital storytelling role as a counterpoint to the explicit story, and as a tone-shaping tool to subtextually guide viewers to more complicated emotions. Linh Che’s parents are quite entertaining—they are charismatic and funny in a deadpan way, and over 50 years of familiarity has honed their partnership as they finish each other’s sentences and riff off each other humorously. But, perhaps due to their 50+ years of distance from the story, or the stoicism demanded of them over the years as immigrants, they do not seem interested in engaging deeply in the immediately apparent and messy conflicts that the film implicitly presents, and which we, as sophisticated viewers, automatically bring to bear.

Unremarked upon in the narrative, the deployment of home video rebuts the subject’s assertion that they “were scenery” by wordlessly evoking their full and complex lives.

Interrogations of colonial power, both hard and soft, questions of representation and what media depictions reinforce and what they elide, master narratives around our communal understanding of the war and its role in American history, and the outsized presence of Apocalypse Now in the shaping and formation of these are obvious, but repressed in the surface story presented by Che’s parents. A different, more conventional version of the film that centers its subjects more and simply revels in their presence would still be interesting and entertaining, but would likely fall short of “great”. It is the challenge and responsibility of the film’s visual approach to unearth these unspoken themes, and in doing so, fulfill the project’s grander ambitions of revealing what History has obscured.

It is a hard challenge, especially for a short, but Radcliff is well-suited to the task. We’ve been acquainted with his filmmaking for 15 years, since his festival breakthrough, The Strange Ones, which, in a scripted context, accomplished many of the tasks demanded of We Were the Scenery—a masterful control of tone, a facility with subtext, and the ability to infuse complicated emotions into material that refuses to be explicit about them. The product of four years of development, this film’s release in festivals this year coincided with the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, and its success—awards at Sundance, Dokufest, Galway Fleadh, and selection to the Doc NYC and Cinema Eye Honors short lists—have positioned it as a top contender for Oscar this year. The team receives our full endorsement, as We Were the Scenery has the audacity to tackle some of the most complicated themes of our modern world, yet the humility to know that they must be accessed via subtler channels than logic.

Jason Sondhi

Jason Sondhi